Will Brexit trigger the Africanisation of Europe?

One reason why the UK might want to leave the EU is that the EU is an ‘untransparent, ineffective juggernaut’. However, the African experience shows that a web of smaller organisations might be even worse. Unfortunately, an African-style web is where Europe might end up after a Brexit.

Until recently, there seemed to be a consensus in Europe. To weather the storm of globalisation, European integration was crucial. Moreover, the EU had to serve as the main bloc of integration. The function of the EU as the anchor point of European integration was confirmed on several occasions. After the USSR-collapse, several Eastern European countries applied for membership, resulting in 13 new EU-members since 2004. Even today, the EU sets the tone by urging Switzerland to ensure EU-compliance of Swiss legislation.

It seems as if the “EU standard” is going astray.

Indeed, there are plural special-purpose organisations in Europe, but it is clear that the epicentre of European integration is “Brussels”. However, this has not always been so clear. In the 1950s, there were multiple European integration projects. First, there was the ambitious European Economic Community, started by the “Inner Six” (BeNeLux, West-Germany, France and Italy). The EEC eventually became the EU. Second, there was the less ambitious European Free Trade Association, created by the “Outer Seven” (including the UK) in the context of the Marshall-plan.

The spurs were taken out of EFTA when its biggest economy, the UK, acceded to the EU in 1973. Today, EFTA is relatively insignificant, consisting of Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein. By acceding, the UK recognised that the EU was the European standard.

However, it seems as if the ‘EU standard’ is going astray. Again, it is the UK that bells the cat, by organizing a referendum on Brexit. Moreover, Brexit might have a spill-over effect to other Eurosceptic countries. Former Pentagon adviser Robert Kaplan argues that this might result in European integration at different speeds, comprising a core Europe and a diverse periphery.

One of the reasons why the British might want to leave the EU is the EU’s regulatory and administrative burden. Question is whether leaving the EU and potentially undoing the EU standard will result in more transparent European integration.

Africa

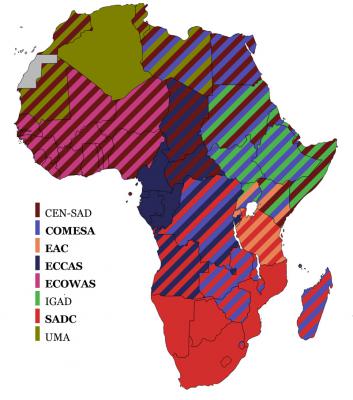

Africa is poorer and more diverse than Europe. Moreover, it has a larger population and area than Europe. Yet, a clarifying comparison can be made between Africa and Europe (both comprising about 50 states). African integration has been less far-reaching than European integration and performed poorly in economic terms. This might be caused by poverty or corruption, but there may also be another reason why African integration does not deliver: there is no standard in African integration. There are too many badly coordinated integration projects. For those who think the EU is complicated, an overview.

Map of the building blocks of the AEC.

In attempt to create an African Economic Community, countries have been organised in economic “building blocks” per sub-region (West-Africa, Central-Africa…). However, some building blocks overlap, while others are dormant. Kenya for instance is part of EAC, COMESA, IGAD and CEN-SAD, organisations with approximately the same function.

On top of that, there are plural local organisations for economic cooperation (cf. BeNeLux Union). Examples are GAFTA, CEPGL, COI, LGA and MRU.

Moreover, African countries aspire to a common currency and have created not one but several organisations for this purpose (CEMAC, UEMOA and WAMZ), resulting in several common currencies (Western and Central Franc CFA). Intellectual property is governed by not one, but by two extra international organisations: ARIPO and OAPI. The overarching African Union is active in several fields, via programs like NEPAD and CAADP and helped by among others UNECA of the United Nations.

As a consequence, some packages of related legislation are harmonized by more than one international organisation. For instance, ECOWAS, OAPI, ARIPO, EAC, COMESA and SADC have legislated in an attempt to harmonise African legislation on seeds. Kenya, to take a particular country, has to take the seed norms of ARIPO, EAC and COMESA into account.

Benefits of clarity in integration

It is conceivable that Brexit might eventually result in an African-style mishmash

It is conceivable that Brexit might eventually result in an African-style mishmash: a web of treaties between an abundance of free-trade areas, custom unions and special-purpose international organisations. Most probably, such a European patchwork would still link to a (much smaller) core-EU. It seems unlikely that such an approach to integration can deliver the administrative transparency the British want. Or might they expect to profit from this divide-and-rule strategy?

Lodewijk Van Dycke is PhD Researcher at the KU Leuven Centre for IT & IP law. He studies the rule of law in the context of the legislation on seeds in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Maak MO* mee mogelijk.

Word proMO* net als 2793 andere lezers en maak MO* mee mogelijk. Zo blijven al onze verhalen gratis online beschikbaar voor iédereen.

Meer verhalen

-

Report

-

Report

-

Report

-

Interview

-

Analysis

-

Report

Oxfam België

Oxfam België Handicap International

Handicap International