Gie Goris was van december 1990 tot september 2020 voltijds actief in de mondiale journalistiek, eerst als hoofdredacteur van Wereldwijd (1990-2002), daarna als hoofdredacteur van MO* (2003-juli 20

100 years of consciously planned division in the Middle East

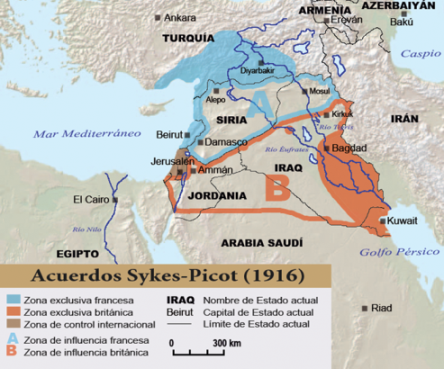

On May 16th, it was exactly one hundred years ago that a British and a French diplomat drew the borders of the contemporary Middle East and, in doing so, were responsible for many of the conflicts of the past century. Bruno de Cordier and Tom Kenis weigh the importance of Sykes-Picot.

On May 16th 1916 the French negotiator Georges Picot and the Brit Mark Sykes secretly agreed, on behalf of their countries, on a division of the territories which back then still belonged to the imploding Ottoman Empire. In 1920 that deal was made official with the Treaty of Sèvres. France and Great Britain divided the region into spheres of influence, based on which countries like Syria, Libanon and Iraq were created.

‘Sykes-Picot’ was the basis for the region’s political and social history of the whole century. A century of nonstop conflict, repression and riots. The discovery of oil in the 1920s only increased the region’s strategic importance, and not always to the benefit of the local population, according to David Criekemans in his MO*paper last year.

ISIL’s first video showed how the movement swiped away a border post between Syria and Iraq

The recent developments in Syria and Iraq set off the implosion of the Sykes-Picot arrangements in the Middle East. ISIL’s first video showed how the movement swiped away a border post between Syria and Iraq. The creation of the caliphate that IS declared shortly after was an explicit statement against the division the French and the British had imposed in 1916.

Today’s one hundredth birthday of Sykes-Picot calls for some reflection. Two MO*academy members give their answers to our questions.

Divide ut impera

Sykes-Picot is generally seen as a divide-and-conquer strategy of the imperial governments in Paris and London at that time. What was Europe’s interest in a divided Middle East? And did its strategy “work”?

Tom Kenis: Until the decision to dissolve and divide the Ottoman Empire, its subsistence was seen in function of it being a buffer against the Russian spread towards navigable waters, but also as a negotiator between competing European states. In that sense, we should rather think of the Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916 in line with that European rivalry: it was more a strategy to divide the Middle East among competing European states, rather than a strategy to ‘divide and conquer’ the Middle East itself. It further divided one of the last colonial booties, if you like.

Due to the Russian revolution, the country missed out on its slice of the cake

In the agreements, Russia was even rewarded with exactly the thing the weakened Ottoman Empire had long been tolerated and even supported for: Istanbul, and the waters between the Black and the Mediterranean See, and Armenia. However, due to the Russian revolution, the country missed out on its slice of the cake, unlike France and Great Britain who were happy to devour theirs.

The Sykes-Picot agreements of 1916 collided with the League of Nations mandates of 1918. From the early start it was clear that France wanted to annex the territories it had been allocated, as it did with Tunisia and Algeria. Meanwhile, Great Britain’s infamous Balfour Declaration of 1917 promised to establish a national home for the Jewish people in what would later become known as Israel. Sykes-Picot also ran counter the Hussein-McMahon correspondence (1915-1916), which formalized the promises the laurelled Lawrence of Arabia had made to the Arabs to give them an independent Arab nation in exchange for their support against the Ottomans.

These contradictions lay bare a certain nonchalance, a sort of ad-hoc way of thinking and a grotesque ignorance of the Middle East, its inhabitants and the existing power structures. These had taken root during the century-long decline of the Ottoman Empire and were often based on structures that existed way before the Turkish dominion. The British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour even suggested during the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 that it was literally impossible to fulfill all western promises and declarations, “partly because they are incompatible with each other and partly because they are incompatible with facts.”

Western promises and declarations were impossible to fulfill, “partly because they are incompatible with each other and partly because they are incompatible with facts.”

The need for a real divide-and-conquer strategy only came in 1930s with the discovery of important oil reserves in Saudi Arabia. At that time, the main political boundaries in the Middle East had already been drawn and consolidated. But that did not make them less useful with the newly-found energy sources in mind, which would become increasingly more dominant in the way the West looked at the region. Competing individual nations were much more preferable than Pan-Arabism, which the Egyptian president Nasser would later defend. It was he who united Egypt and Syria between 1958 and 1961 to form the United Arab Republic and, in doing so, symbolically abolished Sykes-Picot for the first time.

The (again) secret agreement between Great Britain, France, and Israel to attack the dangerous Nasser in 1956 should be seen against the same backdrop. Egypt or Syria may not have had that much or even no oil at all, but too much solidarity or even a coalition with Arab countries had to be avoided at all cost. Israel, which was after all a product of Sykes-Picot as well, got to secure the region in the broadest sense (including its oil) many times afterwards. And when it did, it was always provided weapons and encouraged by Europe and, increasingly, by the US.

Bruno de Cordier: Europe was very much aware of the formidable mobilising power of the Islam and the caliphate. In that sense, Sykes-Picot “worked”. But I do wonder whether ‘Sykes-Picot’ has not been used as a lightning rod or an alibi onto which Arab leaders and movements can shift the blame for their own failure or as even an excuse for their own actions.

Local political movements, aspiring monarchs, Bedouin tribal chiefs and Kurdish Aghas were treated as powerless nobodies in the entire Sykes-Picot process.

The Middle East was fragmented long before Sykes-Picot and the implantation of the classic European empires. And the Ottoman Empire had been stuck in a period of decadence for quite a while, which in fact all empires and superpowers go through sooner or later.

Besides, every system of dominion can only be built with the active and attentive participation of local interest groups and their members. That was as much the case for Sykes-Picot as for the Caprivi Strip or the Durand Line, to name just a few examples. Local political movements, aspiring monarchs, Bedouin tribal chiefs and Kurdish Aghas were treated as powerless nobodies in the entire Sykes-Picot process.

A rude and patronizing underestimation of their position and their abilities! The same can be said for the Wahhabi movement and the Bedouin tribal elites in the Njed, the centre of current-day Saudi Arabia. As a matter of fact, there had already been nationalistic movements in the entire region since the nineteenth century, who wanted to jump on the momentum of the fall of the Ottoman Empire after WWI to put their own project into practice.

A logic of colonialism

Were there alternatives to Sykes-Picot’s approach to re-draw the Middle East after the fall of the Ottoman Empire?

Tom Kenis: It’s difficult to think of an alternative to a policy that consisted and still consists mainly of alternatives, i.e. contradictions. At the time, the British navigated constantly between the self-determination some had promised the Arabs and France’s traditional colonial model. Britain’s interest in the Middle East – in the pre-oil era – was mainly to secure traffic to India, its crown jewel.

That’s why they preferred to exert their control indirectly, by supporting friendly and relatively weak regimes, for instance, and in many other ways. That model was probably too difficult to maintain given France’s more assertive approach. The latter had already annexed Algeria and Tunisia and now had its eager eye set on Syria and maybe even on neighbouring states, which were indirectly controlled by the British.

The real tragedy of the devolution of the Ottoman caliphate in March 1924 was that the holy places of both Sunni and Shia Islam and the pan-Islamic diplomacy were suddenly in the hands of the Wahhabi oligarchy in Saudi Arabia

Bruno de Cordier: The real tragedy of the devolution of the Ottoman caliphate in March 1924 – not due to the Sykes-Picot treaty but to the Turkish republicans, by the way – was, besides the ‘decapitation’ of the Ummah, that the holy places of both Sunni and Shia Islam and the pan-Islamic diplomacy were suddenly in the hands of the Wahhabi oligarchy in Saudi Arabia. This institution has so far never intended to overtake the Ottoman Caliphate, but once the current oligarchy falls (which will happen), a future coup in Saudi Arabia and even in a confederacy with Pakistan cannot be ruled out.

What should have been decided instead of ‘Sykes-Picot’ is easily said afterwards and, without the technological ability to time-travel, it can no longer be implemented anyway. But there will nevertheless continue to be efforts to reinstate a legitimate caliphate in a particular geographical region. Which is in itself a justified cause, as long it doesn’t end in an Islamic interpretation of globalism by striving towards a global caliphate.

The British and a nation for the Jewish people

How strong is the coherence between Sykes-Picot and the Balfour Declaration?

Bruno de Cordier: The Balfour Declaration of 1917 was made to mobilize the Zionistic movement and Jewish financiers in Europe and North America for the British war effort. Although the Zionistic movement or some of its partisans probably saw the reallocation of the region intended by Sykes-Picot in 1916 as an opportunity, an objective chance to build a Jewish nation in the Holy Land.

Tom Kenis: As I mentioned before, the British were meddling between two opposites, namely the Sykes-Picot agreements and the McMahon-Hussein correspondence. Without Sykes-Picot there simply wouldn’t have been the option of a Balfour Declaration. After the Sykes-Picot model was accepted, there was a growing need to give a more concrete interpretation to the ‘British’ region.

The British believed that turning it into a Jewish homeland would give them a local ally. The British Jews who urged for a British policy of the kind were usually rather wealthy, well-integrated citizens– perfectly British, so to speak. An entity led by them had to be on the same wavelength as the ‘motherland’. In 1956, during the Suez crisis, that would very much be the case, indeed.

Artificial states subjected to seismic changes

Historical constructions will eventually create real experiences and institutions. The (partially) artificial borders and nations that resulted from Sykes-Picot are by now a century old and have in many cases led to real nationalism. In other words: is it still feasible today to undo the colonial layout in the Middle East and is there a platform for it?

Bruno de Cordier: Yes and no. The Westphalian nationalism in the Middle East was probably much stronger in the 50s and 60s than it is today. But to undo the current configuration you also need one state that paves the way. To lead such a project, it must not only have sufficient economic power but also ideological and cultural charisma. Currently, there’s no state that’s up to that job yet.

Westphalian nationalism in the Middle East was probably much stronger in the 50s and 60s than it is today

Many commentators have been predicting the downfall of Assad’s government in Damascus since 2011, which they believed would only be a matter of months. A question I ask myself is whether it can survive on raw repression and the help of Hezbollah, Iran and Russia only. Especially with all the destructions caused by the war and the international isolation it brought them. That seems rather improbable, so it must mean the government has some support among its population, not only among Alawites but also among Sunnis and Christians.

Tom Kenis: There’s little purpose in wishing the Sykes-Picot agreement and all its negative consequences would never have taken place. History’s there so we can study it as accurately as possible and learn from it, not change it. You could say European nationalism caused a lot of damage both in Europe and the Middle East. Through trial and error, Europe is still trying to cope with the heaps of victims it made, which it is currently doing by offering a supranational story. A similar challenge awaits the Arab states. The difference is that many of those states can only become autonomous to a certain degree.

Especially a lot of smaller states would not exist today without the strategic support they get from countries in and outside the region. One example is Israel, but also Kuwait which was almost wiped off the map in 1991. And how independent is Egypt really, if you take into account the billions of dollars it’s been getting from the US every year since 1980? All of that in exchange for peace with Israel (and for the promise that they spend the money in the American ‘weapon souk’). Quid Palestinian self-determination?

The Middle East is currently going through seismic changes. Some borders will probably be re-drawn, for example the one between a prospective independent Palestine and Israel, inasmuch as such a two-state solution is still possible. Will Iraq fall apart into a Shia, a Sunni and a Kurdish part after all? And what with Syria? If you opt for a redistribution of land there, how long can we keep Lebanon together?

Rather than to radically pursue a Middle East that was never ‘Sykes-Picoted’, we should focus on making feasible compromises

Rather than to radically pursue a Middle East that was never ‘Sykes-Picoted’, we should focus on making feasible compromises: federal structures for ethnically and religiously diverse states; more powerful regional coalitions (more effective than the Arab League); difficult processes of democratization rather than a fictitious sense of security in the shadow of men with reflective sunglasses; pragmatic solutions to old wounds like the Arab Peace Initiative with Israel, which has been on the table since 2006; etc.

Saudi Arabia is financially preparing full speed for the post-oil era. And strategically it is doing so as well. It is, for example, building an immense weapon arsenal for a time when their big buddy on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean has neither the means nor the interest to help ensure the country’s energy supply. And the countries that don’t produce oil had better brace themselves too. Despite the current frantic activity, there will likely be less Western interference in the decades to come. Whether and how the artificial nations will cope remains to be seen. Maybe then we will finally find out what the Middle East would have looked like without Sykes-Picot.

Modesty first, and lots of it.

What would be a fit way for European countries to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Sykes-Picot?

Bruno de Cordier: Sober-minded retrospection that underlines the role and responsibility of both European and the Middle Eastern actors. One that focuses on the issue “now what?” The question is who or what will have to do that for the European countries.

On the 100th anniversary of Sykes-Picot, what the West really needs is a sense of modesty.

Tom Kenis: On the 100th anniversary of Sykes-Picot, what the West really needs is a sense of modesty. It may be nonsensical to expect a mea culpa for the agreement made one hundred years ago, especially since the intervention in the region never really stopped. Commemorating the event should therefore also mean we re-think our current ad-hoc policy, the way we stumble from stretcher to flashpoint and back, just like the British did one hundred years ago.

Examples galore: the support, or in other words selling weapons for billions of dollars to ‘strong men’ to ensure ‘stability’ in the region and then ending up surprised when everything goes wrong. Throwing bombs on a country you’d prefer wouldn’t send so many refugees. History, as I said earlier, is there to learn from. The longer Europe postpones growing up, the uglier its portrait in the attic will get, reflecting that we are in fact the Middle East. ISIS is really just us.

ISIL is actually destroying the idea of a caliphate

When ISIL first came to our attention in the summer of 2014 and declared its caliphate shortly after, the organization – and many international commentators with them – made reference to the lasting damage Sykes-Picot had caused and to the open, festering wounds of the colonial period. Today, we hear almost nothing about that anymore, not even from ISIS. Why is that? Was the treaty not that crucial a factor after all?

Bruno de Cordier: ISIL, with its reinvention of the Thirty Years’ War (this time between Sunnis and Shias) has so far caused more damage to the Islam as a global image and ideology and to the concept of the caliphate than Sykes-Picot ever did.

Maak MO* mee mogelijk.

Word proMO* net als 2793 andere lezers en maak MO* mee mogelijk. Zo blijven al onze verhalen gratis online beschikbaar voor iédereen.

Meer verhalen

-

Report

-

Report

-

Report

-

Interview

-

Analysis

-

Report

Oxfam België

Oxfam België Handicap International

Handicap International