Fleur Leysen heeft een achtergrond in communicatie en Conflict & Ontwikkelingsstudies.

The Lost Voices of Dzaleka

Built for 8,000 people in need, the ‘temporary’ refugee camp Dzaleka in Malawi quickly turned into a permanent slum where 52,000 forgotten refugees are forced to live together.

© Fleur Leysen

The Dzaleka refugee camp in Malawi is home to more refugees than the camp can handle, blogger Fleur Leysen noted during her visits there. The temporary camp was built for 8,000 people in need, but quickly turned into a permanent slum housing 52,000 forgotten refugees.

Shadrack stares at the dusty streets of the camp; offering him a fleeting glimpse of his apparent eternity. He then lowers his head, his face of fatigue peeping from under his cap. Shadrack is exhausted, yet smiles at me cordially now. He is desperate to tell his story. A story that chills to the bone.

Shadrack, though a wizard of words, seems to struggle at first during his recital. The words seem to be stuck in his heart, his soul and in his entire surroundings. And then he loses himself, or better more, finds himself again in his poetry. As the words spill out, a whole world originates from them. Through his passion, his tears can be heard. Tears for a lost family, a lost homeland and a lost life.

It has been years since Shadrack fled DRC[*] with his mother and two sisters. After his father got brutally murdered by armed men, it became clear that their homeland could no longer provide a safe space for them.

Only a week after arriving in Dzaleka, his mother died as well, fatally injured during the same armed confrontation. Losing both of his parents, Shadrack found himself as head of the family in a country that did not welcome him, in a place that robbed him of his aspirations and his future.

Namad fled DRC as well, leaving behind South Kivu due to the protracted violence. For decades now, the situation in the Kivu’s has been unpredictable, unstable and predominantly fatal. Years after the initial Kivu conflict the violence lingers on, spreading through the region as a deadly echo. A slumbering shadow that makes Eastern Congo uninhabitable.

While fleeing the country, Namad got separated from his family. Stranded in Dzaleka, he got the news that his family was already in the camp. After a lonesome journey, the picture-perfect reunion with his family was unfortunately disrupted by the news that two of his sisters were missing.

To this date, their whereabouts are still unknown. ‘I still remember the rollercoaster of emotions. The feelings pulled on me from all sides and I didn’t know what to feel first. I had my family back, but we will forever be incomplete.’

Namad grimaces when he talks about his sisters. Every day he sees the grief of his mother for her lost children and for the fate of the children that are still around her. But it is his father’s sorrow that concerns him the most. His father, beaten down by the refugee life and the loss of his daughters, could see no more light at the end of tunnel.

He is doing slightly better now, as the immense perseverance of Namad inspires him to give life another chance.

© Fleur Leysen

A Safe Haven?

The despair of Namad’s father is no exception. Refugees worldwide have to fend for themselves and are even being pushed into oblivion by governments, security forces and the public opinion. The massive influx of Ukrainian refugees throughout Europe has once again highlighted the deplorable circumstances refugees face upon arrival in a new country.

However Ukrainian refugees might be welcomed with slightly more open hands than their counterparts of colour, their lives will forever be dismantled by the trauma and its consequences. It is therefore crucial to consider the enormous impact the refugee stigma and camp life has on one’s life.

Though overshadowed by the Ukrainian crisis, the chronicle of Malawi’s refugee camp is similarly bleak. Malawi might be infamous as one of the poorest countries in the world, the relatively peaceful environment make it appear to be the safe haven in Africa for many people on the run.

Battered from the conflicts and tragedies in their homelands, people from mainly DRC, Burundi, Rwanda, Ethiopia and Somalia find their way to the Southern African country. However, arriving at the Warm Heart of Africa, they are directed to Dowa District, with a one way ticket into the already overcrowded Dzaleka Refugee Camp.

Set up by UNHCR in 1994, Dzaleka Refugee Camp was supposed to host 8,000 people. Decades later, the camp overstretched its capacities and turned from a temporary settlement into a permanent village for the forgotten 52,000 refugees currently residing there.

You might not find the archetypal image of a refugee camp when strolling down the streets of Dzaleka, yet its residents share a comparable burden. They are not forced into makeshift tent villages nor do they have to encounter severe police brutality on a regular basis. Still, their human rights are perpetually violated.

The residents of Camp Dzaleka are not forced into makeshift tent camps, nor are they subjected to brutality such as excessive police brutality. Yet their rights are constantly being violated.

© Fleur Leysen

The Prisoners of Dzaleka

The people of Dzaleka are systematically oppressed by structural restrictions, inhibiting any chance of a decent, humane life. Whereas the incoming refugees used to be able to move around more freely and integrate to some extent within mainstream society, a recent ministerial act ordered all refugees – including the ones living outside the borders of Dzaleka for many years – back into the squalid camp.

And so the ‘ghetto of Dzaleka’ was created. Its residents are no longer allowed to set up businesses outside the camp and freedom of mobility has become but an illusion for the people of Dzaleka. ‘This is Kanengo[1]’, Namad points at the street in front of him. ‘Since we are not allowed to leave Dzaleka, we created our own Malawi within the camp.’

Moreover, food and water have become scarce due to donor fatigue and access to sanitation and medical facilities remains difficult. Further, with few options to build a business or livelihood, many people resort to negative coping mechanisms and desperate means to survive. Hence, human trafficking, drug abuse, child labour, domestic violence and prostitution are rampant in the camp.

Life has stood still and the destructive dissolution over the years can be seen in every corner of the camp, as well as on the faces of many of its residents. New generations are born a refugee in the camp, children are forced to waste their precious childhoods and seniors have to spend their final days in the desolate place.

Mikelange is “lucky” to sell donuts right on her doorstep.

© Fleur Leysen

The Kids Aren’t Alright

The Congolese Mikelange knows these struggles all too well. Stranded in Dzaleka since 2015 with two infants to care for and no stable income, she was ‘lucky’ enough to be able to sell doughnuts on her front doorstep. ‘I will face whatever comes my way as a single mother in the camp, no matter the pressure put on me. Making these doughnuts saves me from ending up in prostitution, like so many others. What would happen to my children if I were to end up there and got infected with some sort of sexual disease?’

Despite her own fierceness, Mikelange’s concerns are suffocating her for watching her children grow up in the camp, where they are susceptible for excessive drug and alcohol abuse and where their dreams grow smaller each day.

Birindwa, who also fled from DRC, shares her concerns. He has been living in the camp for six years, making a living for his family by working as a bricklayer As father of many, he is determined to build a better life for his children. He understands that education is the backbone of a hopeful future, so he will do anything in his power to get his offspring into schooling – no matter where he lives. But life in the camp seriously obstructs these ambitions.

Brindwa fled from DRC to Malawi, where he has been trying to build a life for his family as a bricklayer in Dzaleka for six years. As the father of many children, he is determined to provide a better future for his posterity.

© Fleur Leysen

Though there are some schools to be found in Dzaleka, only an estimate of 36% of school-age children regularly attend them. School materials, teaching resources and certified teachers – who are willing to work for a pittance – are almost impossible to find, inhibiting truly qualitative education. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic made access to schooling even harder.

Further, the camp knows many school dropouts, as parents often find themselves unable to make ends meet and children have to help generate money. Boys either have to support their parents by doing menial labour or find themselves struggling with excessive alcohol or drug abuse. On the other hand, teenage girls in the camp often drop out of school as they resort to ‘survival sex’ and do not return when they are pregnant.

Noémie[2] is seventeen years old and mother to an infant son. The father abandoned her after finding out she was pregnant, a fate many women encounter in the camp. She does not have any family to fall back on and lives alone with her baby in a ramshackle house that is about to collapse due to the heavy rains.

Noémie dreams of becoming a nurse, but cannot afford to go to school because she has to take care of her son. MuTu, an organisation by Dzaleka youth which targets orphans and vulnerable children, is now looking after her – hoping that the new-born mother soon will be able to control her own destiny again.

© Fleur Leysen

The voices of Dzaleka in this article underscore what history has proven again and again; isolating people into ghetto-like settlements has a counterproductive effect, both on the lives of the confined persons as society as a whole. The hardship of dwelling the camp generates many other hurdles for the people of Dzaleka – education, employment, political participation, discrimination and the heavy burden of building an identity when everyone seems to deny your right to exist.

The continuous waste of Dzaleka’s tremendous potential is not only a pity, it also thwarts any meaningful development of the nation.

A Star is Born

The camp hosts thousands of people with different backgrounds, cultures and dreams. A multicultural melting pot, so to speak. However, all of them share the burden of their untold stories behind their lips. The tragedies of their countries will remain a vital part of the people of Dzaleka. Still, they do not give up.

Shadrack and his peers are determined to pave the way out of the camp and away from the stigma the refugee life entails. And this way forward will be achieved by using the one thing no country will ever be able to take from them: their talent.

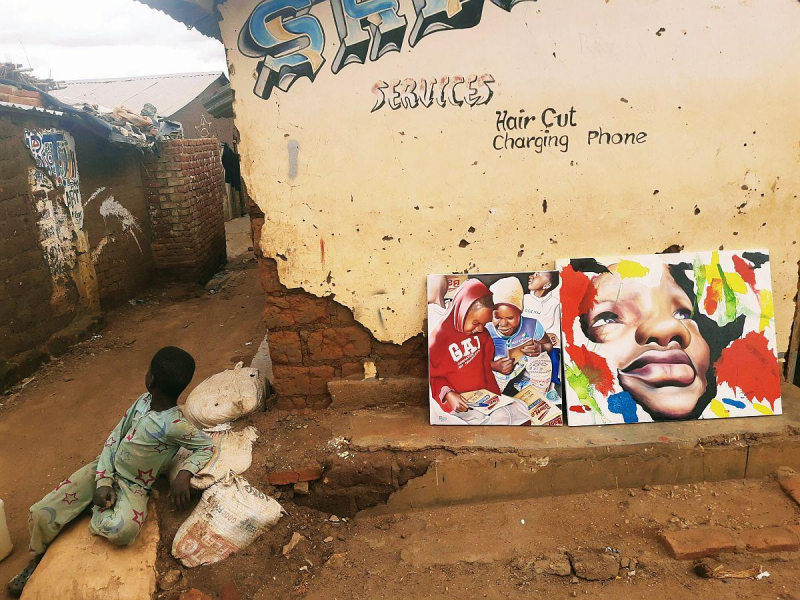

Many young people in Dzaleka turn to art to escape the grim reality, or to make their mark.

© Fleur Leysen

In the forgotten world of Dzaleka, young people found a way to create their own world, their own place to explore – through the healing power of art; the solace found in the warmth of a cultural embrace.

In Belgium, the cultural sector has been in dire straits for a while now. This has, however, exacerbated the understanding of the vital importance of culture for the bigger audience in the country. People have realized culture is not mere entertainment, but entails an endless source of empowerment. Art as resistance is nothing new. Through ‘artivism’, many artists, activists and vulnerable groups around the world have claimed their seat at the table, and forgotten people have given purpose to their lives once again through the use of art.

In Dzaleka, many youngsters have also resorted to art to cope with reality. Abstracted poets wander through the camp, with a mind never at ease. ‘Penny for a thought’ might make them the richest men alive. Over twenty dance groups are scattered around the camp, periodically breaking out in an aggressively passionate dance; on the sports fields young athletes gather to lose themselves in the game and kids get their hands dirty while creating paintings of an imagined world that seems out of their reach.

The youth of Dzaleka understands the melancholic power of the camp and find that culture brings them serenity, a way to deal with stress and boredom. Overall, it keeps them away from the many hazards that lurk around every corner of the camp.

The Congolese Aaron[2] is one of the many artists within the walls of the camp. As the oldest son of ten children, he became the man of the house after the demise of his father. He eases the burden on his shoulders through his artwork and inspiring texts. ‘One day, I will be an international artist, far beyond the borders of Dzaleka’, he claims firmly.

The people of Dzaleka cherish the enormous pool of talent. Through cultural movements, events and festivals such as Tumaini, they have found an outlet for their potential; a way to make people listen to their past lives, present tragedies and future desires. These festivities aim at bringing harmony and a growing tolerance between the refugees and the host community. A celebration for inclusiveness and solidarity.

© Fleur Leysen & Shadrack Lokwa

No Longer Refugee

Malawi has a great vision for the future; building up the country by 2063 and leaving no one behind. Rests us only one question: if Malawi is indeed set on becoming a middle-income country by 2063, will it ensure that all of its inhabitants are part of this evolution – including the people of Dzaleka?

Currently, the government is developing a plan to move a part of Dzaleka’s population to Karonga, a district located at Lake Malawi. This might lighten the burden of overpopulation in the camp. However, this will not bring about change, neither for the refugees or the host community.

In order to break the downwards spiral, the government needs to ensure that future generations do not have to grow up in any camp. In order for the whole country to benefit from the potential of Dzaleka’s people, they should be granted their basic human rights – and hopefully beyond basic.

The people living in the camp are not going anywhere, nor will new-coming refugees stay away. For the sake of humanity, the government needs to take its responsibility and ensure a decent life for these people, rather than confining and neglecting them.

They have been ignored for too long and as long as the sound of their voices is limited to the borders of the camp, the many generations in Dzaleka will not be able to break from their vicious cycle.

Overall, the residents of Dzaleka should be incorporated into mainstream society, where they will be able to truly develop their talents, flourish and maybe one day, one of them will stand up as Malawi’s greatest poet, musician or athlete.

[1] Kanengo is een wijk in de Malawische hoofdstad Lilongwe. De straten in Dzaleka zijn omgevormd tot allerlei bekende gebieden of districten in Malawi, zoals Lilongwe, Dedza, Blantyre etc. ↑

[2]Noémi en Aaron zijn fictieve namen om de identiteit van de getuigen te beschermen.↑

The situation in DRC is still one of the biggest humanitarian crises globally. Eastern DRC keeps suffering from excessive violence by armed groups, both national as foreign militias. Since 1996, the numerous conflicts in the country have presumably claimed the lives of 6 million people.

The most affected areas are North and South Kivu. “Over 130 armed groups are fighting for countless reasons in Congo’s eastern Kivu provinces, making the region one of the most violent places in the world,” said Lewis Mudge, Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch.

Between 2017 and 2019 (the period in which the people quoted in this article also fled DRC) an estimate of 8.38 per 100.000 civilians were killed, which resonates with some of the biggest contemporary conflicts elsewhere in the world. Many children are recruited for fighting and young girls are abducted to become sex slaves. Abductions are commonplace in the region.

Since 2019, new waves of violence have sparked the Kivu’s. The violence also damages necessary infrastructure and seriously impacts the food security of the population. On top of the armed violence, DRC endured many epidemic crises. The most recent statistics show a total of 864,770 Congolese refugees outside DRC’s borders and about 5 million internally displaced persons.

Maak MO* mee mogelijk.

Word proMO* net als 2798 andere lezers en maak MO* mee mogelijk. Zo blijven al onze verhalen gratis online beschikbaar voor iédereen.

Meer verhalen

-

Report

-

Report

-

Report

-

Interview

-

Analysis

-

Report

Oxfam België

Oxfam België Handicap International

Handicap International