Pieter Stockmans volgt het mondiale optreden van de Europese Unie, het Europese vluchtelingenbeleid, de evoluties in Midden-Europa en de regio ten oosten van de EU.

‘All democrats should stand up now, resorting to civil disobedience if necessary’

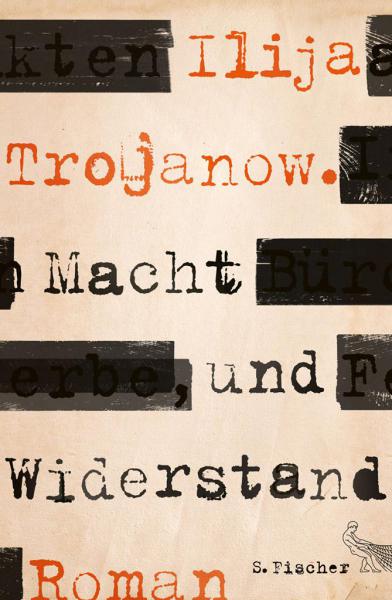

The Bulgarian-German writer Ilija Trojanow worked his way through the archives of the autocratic regime in communist Bulgaria. He draws parallels with the growing autocracy in Europe, and not only with Donald Trump in the United States. A conversation about the illusion of security, the power of the state and the belief in resistance.

Ilija Trojanow

© Ilija Trojanow

‘The mistakes America made in Iraq, it repeated in Libya. And the woman responsible for that will be the next president’, Ilija Trojanow said when we interviewed him. The campaigns for the American presidential election were still in full swing. Just in time, we asked his reaction to Donald Trump’s election as President of the United States.

‘If the president-elect decides to pursue his ridiculously undignified and inhumane plans, real democrats will have to resort to civil disobedience.’

President Trump could mainstream autocracy as a political system in the West. But its slow ascent can be traced back to at least 9/11. Whether it was Bush or Obama, both presidents have gradually expanded the power of an invisible state machinery that dodges democratic control. A Trump presidency will continue to run the same course, simply because the system works almost autonomously. And it gathers information about citizens in the same paranoid way as the communist secret services.

It has to do with the so-called Deep State: the increasing power of non-transparent security services and laws that restrict civil rights and liberties for the illusion of security.

© fischerverlage.de

For his latest novel Power and Resistance, Trojanow combed through the archives of the State Security services of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria and talked to former political prisoners and officials. Original documents from the archives provide an insight into the way power takes root and grows in totalitarian states.

He translated real facts to beautiful literary prose that provides insights, not only into the history of an Eastern European country, but also into the nature of human society.

Trojanow himself got to feel the long arm of the state too. In 2013, he was already interested in the parallels between former communist and modern-day surveillance states. After he had written an open letter to Angela Merkel about the widespread espionage by the American National Security Agency in Germany, he was denied access to the US.

‘It is more than ironic that an author who for years has been speaking out about the dangers of surveillance and the secret state within the state, should be denied entry into the land of the free and the home of the brave’, he wrote at the time.

Trojanow’s life experience is also intertwined with another big challenge of our times: the refugee crisis. As a Bulgarian refugee who grew up in Germany and Kenya, he is the incarnation of the multicultural society. He knows like no other what society has to lose if it turns against diversity.

Xenophobia to buy votes

Fear stirred up by immigration, terrorism and economic insecurity is the main reason for the appeal of authoritarian populists like Farage, Le Pen, Wilders, Orban, Trump,…

Trojanow: … and Alternative Für Deutschland. Fear is one of the most dangerous political terms. There is no way of measuring how big that fear really is, but suddenly every politician can claim people are scared and build their dreamed-of authoritarian policy on that. Suddenly, we all have to be hypersensitive to the so-called fears of our fellow-citizens. Suddenly, we have to “understand” to Trump.

‘Fear is a dangerous political term. Suddenly, every politician can claim people are scared and build their dreamed-of authoritarian policy on that.’

When a child is afraid of the dark, you don’t leave the light on during the night, do you? Otherwise, the child will never learn to overcome its fears. Fears have to be faced, not understood. You turn off the lights, but you do give the child some explanation and context. That way, it will be better prepared to face our complex world.

Is the sense of insecurity not real then?

Trojanow: Yes, it is. Europeans are afraid to lose what they have built. The more prosperous you are, the easier it is to be made afraid in a world with less sense of security and more access to information. Young people are thinking more about their financial future these days and less about ideals and vision for the future.

You said: “The easier it is to be made afraid.” That means it’s a political choice. Another choice would be to take the fear away. How?

Trojanow: By working on solving economic insecurity without inciting xenophobia. By outlining the global context. Countries like Kenya have seen large influxes of refugees for years. But when they suddenly come to Europe, it is the end of the world.

‘Resentment and xenophobia are the new currency. Authoritarian populists will instantly turn them into political power.’

Centre-right parties are copying far-right ones because they are afraid that the far-right will swipe away the centre-right elites.

Trojanow: That’s the political cynicism. Resentment and xenophobia are the new currency. Authoritarian populists instantly exchange them into votes and political power, which they then use for anything but offering real solutions to the people.

Instead of turning to xenophobia themselves, how should democrats deal with immigrants in a better way?

Trojanow: By no longer talking about cultural integration, but only about social emancipation. Look at New York. There, people live together in one city, hold on to their own cultures and are still part of one overlapping American identity.

I’m a refugee myself. I know how ridiculous it is to expect refugees to leave their past behind and embrace a new identity. That won’t happen. What we need is a policy that assures all citizens can join in, live up to their own potential and, in doing so, contribute to society. That will automatically lead to social peace. But it’s exactly that policy we’re lacking.

The paranoid surveillance state and its subjects

Since 2015, the year Europe had to deal with terrorist attacks as well as a larger influx of refugees, European and American leaders have been framing immigration as a danger to national security. And people are willing to give up their own freedoms for security.

Trojanow: In 2010, before the revelations by Edward Snowden and WikiLeaks, I already warned against what would happen if we let the power of the surveillance state grow. My book Attack on Freedom: The Surveillance State, Security Obsession, and the Dismantling of Civil Rights was sneered at in some circles. And then came Snowden. All of a sudden, the situation turned out worse than people thought and I was no longer the “hysterical alarmist” but an out-dated critic.

Five years later, the powerful superstate controlling citizens instead of the other way round, has become reality. And yes, this surveillance state uses the growing fear of terrorism and the refugee crisis to further expand its power. But that has been going on since 9/11.

In June 2013, Edward Snowden revealed that, since 2007, the National Security Agency (NSA) had been asking internet companies like Google to give the American Secret Service information about internet communication of citizens. The NSA also tapped the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel’s telephone conversations. Even Wolfgang Schmidt, former Stasi lieutenant in communist East-Germany, responded: ‘For the Stasi such a program would have been a dream. We didn’t have that technology.’ Ilija Trojanow became one of the leaders of the protest that erupted in Germany. In his open letter to Angela Merkel he wrote: ‘Citizens of this country want the whole truth. You are legally bound by the Constitution to keep the German people safe from harm. Madam Chancellor, what is your strategy?’ The German parliament started an investigation. Two years later, WikiLeaks revealed that the NSA had been tapping telephone conversations between Angela Merkel and her advisors for years, much longer and on a far bigger scale than was ever believed in 2013.

You write about the paranoia of the intelligence services during communism, and about the modern-day surveillance state in the West. Do you see any parallels?

Trojanow: The fall of communism was not the end of history. Even in the so-called superior Western constitutional democracies people are prone to the fear of losing control, just like in communist regimes. And that can lead to alarming excesses.

A week after I finished writing Power and Resistance in January 2015, I read the US Senate Committee’s report on the CIA’s practices in the years 2000. The CIA tortured prisoners, gave misleading or wrong information to the media, and tried to dodge government supervision. Without exaggeration: three of the arguments the CIA used to defend itself were almost literally the same as Metodi Popov’s, the communist apparatchik in my book.

What were those arguments?

Trojanow: One: it’s about national security, which you cannot leave up to others, not even the government. Two: we protect this country, so trust us. Three: human rights are a luxury we cannot afford when we have to do our job. So even the total violation of human dignity and privacy is considered an expression of patriotism and professionalism.

These officials claim they are protecting my freedom. I tell them: you have no clue what freedom is, you have the mentality of someone who, like a slave, follows a security apparatus in which the state has all the power and citizens have to be submissive and grateful. There is nothing you can teach the free man about the meaning of freedom.

‘We’re going back to the system before the Enlightenment: you only have rights insofar as the state is willing to grant them to you.’

What do these freedoms mean, you think?

Trojanow: That the actions the state takes against its citizens are only legal if they are necessary in a democratic society. That’s not my opinion. That’s the political liberalism on which our society is founded. The burden of proof is on the state, not on the individual.

After the terrorist attacks, the burden of proof shifted to the citizen.

Trojanow: The state doesn’t have to prove anything anymore. Security officials claim they are preventing attacks. But they cannot prove it. Well then, shut up. Politicians use those statements to install draconic laws and increase the power of the state over the individual. And citizens are cheering on the limitation of their own rights.

We’re going back to the system before the Enlightenment: you only have rights insofar as the state is willing to grant them to you. I strongly oppose that. There are universal rights and the state should protect and safeguard them, instead of granting or limiting them if a majority of the people finds it necessary. Not even a 99% majority could limit individual rights. Limiting individual rights is only possible if there is rock-hard proof of its necessity.

Are efficient security services not necessary then?

Trojanow: Yes, they are, but the worst you could do is collecting too much information. That way, you’ll drown in information, which will only make your work harder. Just look at the paranoid communist officials in my book. They sent out informants to take note of every little detail that could be interpreted as a sign of disobedience or deviation. In exactly the same way, officials in our surveillance state are now registering every little ridiculous indication of so-called radicalisation. They are losing energy and manpower they could use to follow up on real threats.

‘More and more citizens are willingly giving up their rights to a powerful state. How many real democrats are left in our society?’

The surveillance state is not a practical tool to keep us safe. It is an instrument of oppression. Most citizens don’t get that. But if that is the case, you are not a free citizen in a democratic society. How many real democrats are left in our society?’

Then Hillary Clinton wasn’t one either, because she did not defend these freedoms. WikiLeaks revealed there were ties between Hillary Clinton and Google, when Google CEO Eric Schmidt was appointed head of the Pentagon Committee: his task was to integrate technology companies from Silicon Valley with the secret service. And Trump too was talking about law and order constantly.

Trojanow: The obsession with law and order goes beyond party lines and dates back to way before Clinton and Trump. Politicians who promise such things in a world full of challenges are cowards. I used to live in Mumbai for a while, where the idea that safety is something you can guarantee is absurd. And, in a way, that was a relief. In Germany, everyone always expects someone else to protect him or her from all the dangers in the world. But that is the mentality of a slave surrendering to the state for the sake of an illusion.

The ugliness of power, the beauty of resistance

That brings us to power and resistance. Your book follows the lives of a government official and a resistance fighter who opposes the government. Why is it important to tell these stories in 2016?

Trojanow: I wanted to investigate the relation between power and resistance through the medium of literature. Through a character that, despite totalitarianism and far-reaching power, still believes in resistance. And a character that illustrates the normality of power. These men of power were no great ideologues, nor were they particularly talented. They were normal, sometimes dumb and had no principles. Your everyday peasant could gain power over an entire state machinery.

Can you understand people who, from a feeling of insecurity, support those in power while those same people in power resort to deeds or words of injustice, racism, sexism, autocracy, repression?

Trojanow: No, I can’t. I know that not everyone has the strength to act in a dignified way. But take my father, for instance: he has no real interest in politics but still has a firm sense of individuality. We have to keep emphasizing every individual’s freedom of choice and responsibility. Opportunists and people who wanted to advance their career under the communist regime consistently sided with the system, even when it governed with cruelty and injustice.

‘No, I can’t understand people who, from a feeling of insecurity, support those in power, while those same people in power resort to injustices.’

Not everyone who sides with powerful people is an opportunist or a career chaser. Take for instance the hundreds of thousands of Americans who were humiliated when they were evicted during the financial crisis in 2008. Maybe they wanted to take revenge and saw Trump as one big fuck you to a system that destroyed their lives? Vulnerable people want to be on the winning side.

Trojanow: I refuse to go along with this. There are always options to say no. Even in Nazi Germany. No one is expecting heroic actions. Even today, you can already start showing dignity and solidarity in small ways that don’t require much effort. If we don’t believe people can do that, that individuals can defend dignity, then we lose faith in humanity. Then we become nihilistic and pessimistic and nothing but a vehicle for autocrats to gain power. And eventually, that will turn against you for the umpteenth time.

Trump offers to protect and save victims if they turn on others and humiliate them. In all conflicts and polarized political systems, leaders use ordinary citizens to fight other citizens.

Trojanow: That was also the intention of the Bulgarian secret services: let’s turn every citizen into an informant so we can gain full control. They had the perverse urge to leave no stone unturned. In the eighties, 1 million Bulgarians were informants in a country with 8 million inhabitants. In every family, at least someone was connected to the secret service.

‘I cannot accept a world that considers steadfastness a flaw. Resistance is the oxygen of democracy.’

You spoke to people who sacrificed everything for resistance, who were tortured and wasted away in a dark prison cell for twenty years. Did you ask them why they didn’t stop believing in resistance?

Trojanow: Yes, but they could not give me a reasonable explanation. They are just people who feel their own wellbeing is tied to a bigger picture. Like Jesus said: “What good will it be to someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul?” (Matthew 16:26).

I cannot accept a world that considers steadfastness a flaw. In communist Bulgaria, compliance was a far greater value. Resistance is a heavy burden and it is easier to just give in. But the 80% of people who think the surveillance state is a good thing are passive people who don’t take part in history. They simply follow the dominant flow in society. I believe in the 20% who can change the course of history without selling their soul to strong leaders. They understand that protest is the oxygen of democracy.

“The superfluous man”

Gage Skidmore (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The superfluous man

Wasting away for twenty years, enduring torture, to then see that the same criminal elite simply stayed in power after the big upheaval of 1989: how can this man just carry on and feel as if his sacrifice at least served some higher cause? Is resistance worth it, with such an overwhelming opponent?

Trojanow: If you cherish your ideals, the question whether resistance is meaningful or if it will lead to anything does not matter. Resistance lifts you up as a human being above the swamp of egoism. Konstantin felt freer in prison than when he came out, because in prison his spirit was elevated. When your body is wrecked to the point where you just walk in line, you’re left with nothing but your spirit.

Of course his resistance was worth the sacrifice. Without people like him, there would be nothing but corruption, the cynical exercise of power, and submission. Their example allows a new generation to dream and develop their own resistance. It is man, with his endless possibilities, against political systems that try to restrict him…

…and that want to get rid of “superfluous people”.

Trojanow: You’re referring to my book The Superfluous Man. One of my readers sent me a message once that he saw parallels between totalitarian states and corporations that, without any moral consideration, put people aside as superfluous. They clear the system of people they no longer consider of any value or use. That will happen more often. Global competition will push companies to fire people and instead automize more and more, just because robots work more efficiently and faster than human beings. That will cause enormous social disasters.

‘If we do not reform our economic system, the votes of these superfluous people will be up for grabs by populists. At the same time, these people will become engines of rebellion: the catalysts for progress.’

According to an authoritative study on automation, 47% of all jobs in the US will become superfluous in the next 15 years. Society is not prepared to give these people a new purpose and prevent them from feeling expandable. If we do not radically reform our economic system, these people’s votes will be up for grabs by demagogues and populists.

“Expandable people” are using democracy to take revenge through demagogues who capitalize on these people’s frustrations. Should we expect more Trumps?

Trojanow: In the short and mid-term, yes. In the long term, history will weed them out. These populists don’t offer any practical solutions. Which will only add to the frustration and disillusionment. But in a way, that’s a good thing: these people will become engines of rebellion, the catalysts for progress.

Translation: Wout Van Praet

Maak MO* mee mogelijk.

Word proMO* net als 2790 andere lezers en maak MO* mee mogelijk. Zo blijven al onze verhalen gratis online beschikbaar voor iédereen.

Meer verhalen

-

Report

-

Report

-

Report

-

Interview

-

Analysis

-

Report

Oxfam België

Oxfam België Handicap International

Handicap International