Gie Goris was van december 1990 tot september 2020 voltijds actief in de mondiale journalistiek, eerst als hoofdredacteur van Wereldwijd (1990-2002), daarna als hoofdredacteur van MO* (2003-juli 20

Two years after Taliban return: these women keep on believing in freedom

© Elien Spillebeen

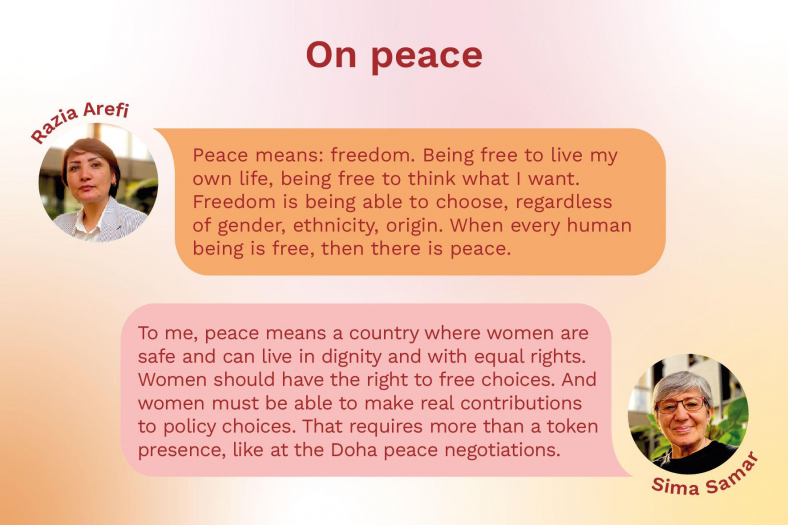

Two years ago, the Taliban returned to power in Afghanistan. Women, minorities and human rights defenders are paying the price, but the militancy of many Afghans has not been broken. MO* talked to two leading women activists, Sima Samar and Razia Arefi: ‘Knowledge cannot be taken away.’

Sima Samar is one of Afghanistan’s best-known women worldwide. ‘I was twelve’, she responds when asked when being female became defining for her engagement. ‘As a girl, I revolted against the restrictions imposed on me purely on the basis of my gender.’

That early resistance later took the form of a degree in medicine, as well as a series of schools and hospitals she founded in exile in Pakistan and later in Afghanistan. After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, she returned to her homeland and became minister of women’s affairs in Hamid Karzai’s first government.

Her outspoken views cost her the ministerial post, but she did continue to lead Afghanistan’s Independent Human Rights Commission for many years and in between also functioned as UN special Rapporteur for human rights in Sudan. Early next year, she will publish an autobiography. ‘It will be a testimony of what I have seen’, says Samar.

Razia Arefi has been living in Belgium for almost two years now, after being evacuated from Afghanistan with a number of Mothers for Peace collaborators. In Kabul, she was the director of that women’s organisation and in 2018 she was a candidate Member of Parliament.

When I asked her ten years ago what she dreamed of, she replied: ‘Peace. A permanent end to the nightmare of Taliban violence. If there is peace, then women can work on their own future plans.’ When I insisted on a more personal dream, she said simply and sincerely: ‘I hope to continue working for women in an honest and sincere way.’ The peace has not come, the commitment never went away.

A nightmare come true

It is a nightmare to live as a woman in Taliban Afghanistan in 2023. In a report published in May, Amnesty International even argued that gender persecution under the Taliban should be investigated as a possible crime against humanity. And in mid-June, independent experts before the UN Human Rights Council called the situation of women in Afghanistan a form of gender apartheid.

Sima Samar is not surprised by the big words in those reports. ‘Afghanistan is currently the only country in the world without a constitution. The only country that bans women from working outside the home. The only country that bans education for girls after primary school. That means Afghanistan today is an open prison for the female half of the population. Denial of basic fundamental rights based on gender is a form of sexual violence, and sexual violence is considered a form of torture. The current policy, in other words, systematically goes against the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.’

Gender apartheid or crimes against humanity: Taliban’s treatment of women is unacceptable

You could also say, I suggest, that the Taliban’s policies towards women are directly against the basic tenets of Islam. Sima Samar certainly agrees. She refers to the first word in the revelation to the Prophet Muhammad: ‘Read’, which presupposes education.

Or to the generalised command to seek knowledge — if need be in distant and then unreachable regions of China. And to the way the hajj is experienced in Mecca without distinction between men and women, Arabs or Europeans. ‘The Taliban go against the very foundations of the faith they claim to defend.’

One ideology, one people, one language

The worst part, Razia Arefi responds, is that this nightmare was perfectly predictable. ‘When Americans and Taliban started negotiating in Doha early 2019, I warned everywhere I could about what was coming, but the international opinion was that the Taliban had changed, that they were making promises about women’s rights, that things would be different this time than in the 1990s.’

Moreover, she adds, the policy is not only against women, but also against minorities. ‘The Taliban’s intent is not just to push through one dogmatic ideology, but to bring the country under one ethnic rule and impose one language,’ she says. Islamisation is accompanied by a Pashtunisation of Afghanistan’, referring to the ethnic group that makes up about half of Afghanistans population but almost all of the Taliban, especially the leadership positions.

Rather, what Sima Samar sees happening is a Pakistanisation of the country — via the spread of Pashtun influence as well as migrants from both Afghanistan and Pakistan.

She looks for the origins of both extreme Islamist ideology and Pakistani influence in the Arab-funded madrassas established along in Pakistan along the border region during the war against Soviet occupation between 1979 and 1989. ‘That is where Afghan children were brainwashed, and we are still paying the price of that Cold War-era foreign interference.’

Repression is not a tradition

Decades of war, insurgency and foreign interventions have deeply uprooted Afghan society. Yet some argue that the Taliban’s policies, including on women, go back to traditional Afghan or Pashtun culture or Pashtunwali.

‘The only valuable thing about that Pashtunwali was the obligation of hospitality,’ Sima Samar responds. ‘But everything else in that cultural code is pretty patriarchal and violent to women. In any case, the Taliban are not representatives of tradition; under no circumstances should they be normalised from that perspective.’

Samar: ‘The Taliban are not representatives of tradition; under no circumstances should they be normalised from that perspective.’

‘I recently heard a Taliban spokesperson argue that rules restricting girls and women to the household are not an attack on their role in society or even on their happiness, because generations of women have found that happiness and role from the kitchen and by the hearth, even during the past 20 years,’ Razia Arefi says.

‘That shows the basic conservative beliefs that drive those in power today. They want to keep women far from education, knowledge and active engagement because they want to avoid critical questions and individual opinions. That is why they are rebuilding Afghanistan into the prison for women that the country is today.’

An unfortunalely situated country

The Taliban’s victory on 15 August 2021 was a sudden thunder, but certainly not from a clear sky. ‘It was not a victory,’ says Razia Arefi. ‘Power was offered to them by the Americans. This also wiped out all the progress of 20 years of education, human rights and democratic debate.’

US President Trump’s peace agreements with the Taliban in 2020 were the false final chord of 20 years of occupation and 40 years of interference in Afghan affairs. And the US was not alone: the Soviet Union, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, NATO countries, Iran and China all had their share in the disastrous half-century that brought Afghanistan mostly violence and war.

Samar: ‘Peace is still conceivable for Afghans, if the people are one’

Is peace still conceivable for Afghans? ‘Certainly,’ responds Sima Samar, ‘if the people are one. And if both regional and international powers are committed to it. But the reality is that Afghanistan is where the tensions between all these superpowers collide.’

Not only that, adds Razia Arefi: ‘Because of the wars, mistrust between ethnic groups in Afghanistan has grown into mutual hatred between Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazara’s, Uzbeks and other communities. These antagonisms were instigated by the leaders of various militias or insurgent groups during the jihad against the Soviet Union, and they remained the fuel of parliamentary politics even under the republic.’

Don’t acknowledge the Taliban government. Ever.

Internal reconciliation between clashing ethnic groups or their political advocates seems far away today. But after 40 years of interference, what can the international community still do?

Arefi: ‘Aid should not be channelled through the Taliban’

Sima Samar has no doubts: ‘Pressure on Taliban leaders must be stepped up, with more individual sanctions and travel restrictions. The Taliban government must also not be recognised, which is crucial.’

‘Meanwhile, more work needs to be done on accountability for war crimes, human rights violations and gender apartheid. That seems to me to be a task for the International Criminal Court. There should also be more international support for Afghan civil society, or what remains of it, in Afghanistan or in the diaspora.’

Should there be more or less humanitarian aid? ‘More,’ Samar thinks, ‘but with much better monitoring. A lot of discrimination takes place in the distribution of aid.’ ‘Moreover, this aid should not be channelled through the Taliban, but should be delivered directly to people,’ adds Razia Arefi.

© Elien Spillebeen

Action and reaction

Razia Arefi is setting up online English courses for girls in Afghanistan, together with Antwerpen University. In a recent online meeting with some 30 girls from Kabul, she noted their pride in the regime’s failure to get international recognition, thanks in part to women’s continued protests — despite repression.

‘It is their resistance and their belief in the future that makes the difference. They do not believe that the Taliban will remain in power and that provides perspective and motivation to keep going.’

‘Some dictators last a very long time,’ Sima Samar sighs. ‘But that doesn’t make them legitimate. And that legitimacy should certainly not be granted to them by the international community. Ultimately, I think laws of physics will also apply here: action provokes reaction. Oppression provokes resistance. Change in Afghanistan will come from below and within Afghanistan itself.’

A safe country?

‘International media should also take care not to function as a platform on which the Taliban can present themselves as reasonable and legitimate leaders,’ Razia Arefi believes. ‘Media should, on the contrary, report more about the regime’s brutality, repression, the self-righteous crackdown on any opinion that disturbs them — even if it is expressed on social media or through closed WhatsApp groups.’

Arefi: ‘How can Afghanistan be a safe country when half the population is confined between the four walls of their own homes?’

That is why, Arefi continues, it was such a shock for her to hear Belgian authorities declare that Afghanistan would once again be a safe country after the fall of Kabul.

‘How can a Western politician say such a thing at a time when half the population is confined between the four walls of their own homes? Fortunately, there are also many people, in this same Belgium, who are putting their shoulders to the wheel in projects to still provide education for girls. After all, they are Afghanistan’s future and hope.’

Maak MO* mee mogelijk.

Word proMO* net als 2798 andere lezers en maak MO* mee mogelijk. Zo blijven al onze verhalen gratis online beschikbaar voor iédereen.

Meer verhalen

-

Report

-

Report

-

Report

-

Interview

-

Analysis

-

Report

Oxfam België

Oxfam België Handicap International

Handicap International