Gie Goris was van december 1990 tot september 2020 voltijds actief in de mondiale journalistiek, eerst als hoofdredacteur van Wereldwijd (1990-2002), daarna als hoofdredacteur van MO* (2003-juli 20

Sulaiman Addonia: ‘Not what should be is important, but what can be’

Sulaiman Addonia, at the ponds of Ixelles

CC Gie Goris (CC BY-NC 2.0)

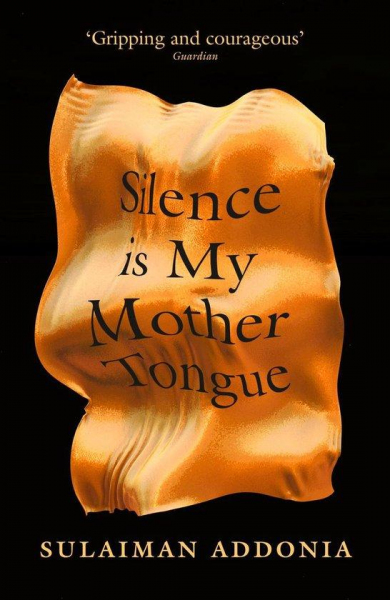

With the novel Silence is my mother tongue, Sulaiman Addonia breaks open our imagination about life in refugee camps. Gie Goris accompanied the author to the dark room where he developed his characters: the ponds of Ixelles. An interview about speaking with silence and sex as spirituality.

We meet on the terrace of Café Belga, at Flageyplein in Brussels. For a suburban barbarian like me, it’s a well-known and familiar place. Sulaiman Addonia prefers Le Pitch Pin, the folksy café across the square, he says after a while. That café became his favorite place after Belga switched to a different brand of coffee than the familiar and valued brand from before. ‘A coffee lover doesn’t understand why such a decision is made’, Addonia shakes his head. I enjoy to be shown the way to the finer taste of life. For that reason alone, we need new Belgians and Brussels residents.

We meet here because his novel Silence is my Mother Tongue was born in the streets, squares and parks of this neighborhood. We talk about Brussels and language, gender and sex, refugees and traditions, and coffee and Pessoa.

The night makes imagination visible

Sulaiman Addonia is a nightwalker. It started when he was a boy, living in Jedda.

‘I can take the same walk every night, week after week, month after month and for years on end,’ says Sulaiman Addonia. ‘At first I thought Brussels was ugly and horrible. Then you see the details that make Brussels special, but after a while the buildings, streets and bushes become so familiar that they speak to me. They become characters that I encounter and I notice how they change.’ Sulaiman Addonia is a nightwalker. It started when he was a boy, living in Jedda.

‘Saudi Arabia is a country where racism and xenophobia are openly professed. Right after I arrived there from the refugee camp in Sudan, it was made clear to me that I should have no illusions: as a black African, I would always be a second-class citizen. Period. My brother and I walked that feeling out of our systems as evening fell. Perhaps because the darkness of night gave us the illusion that our second-class status was less visible.’

In London that walking became exploring, and in Brussels it transformed into something much deeper. ‘When I moved to Brussels, I not only carried a suitcase full of stuff, but also a book that had yet to be written. I didn’t want to subject that story and its characters again to the assumed tastes or comprehension capacities of readers, as publishers or editors think they know. The characters had to shape themselves, but that was much harder than I thought.’

In the end, nighttime Brussels proved to function as a kind of darkroom: the images the writer had in his head were developed in the urban darkness of Ixelles. They took on distinct contours, characters, histories and opinions.

When Sulaiman Addonia begins his circumambulation of Brussels, he first passes by the pensive head of the poet Fernando Pessoa, on a far corner of Place Flagey. ‘My homeland is the Portuguese language,’ it says beneath the imposing statue. For Addonia, it should actually read: ‘My home is language, plural.’

‘I was surprised how easily I could still remember the architecture of the camp.’

From Pessoa, it goes across the stone plain of Flagey towards the ponds of Ixelles. Along the bordered greenery and bubbling fountains are benches that, especially for the nocturnal walker, offer space for dreams and reflection.

In just about everything, this place is the opposite of the Sudanese refugee camp where Addonia spent his childhood and where Silence is my mother tongue is also set: plenty of water, a green setting in the middle of a prosperous city, strollers savouring the pleasure of a free hour or heading to one of the cafe’s or restaurants nearby.

Does he seek out places like this to blow the dust of the refugee camp from his heart and brain? ‘No,’ he replies. ‘That refugee camp was already so far behind me that I had to rebuild it on paper before I could let my characters live in it. At the same time I was surprised how easily I could still remember the architecture of the camp. I have a visual memory and have been shaped by cinema before literature. But compensating for the camp, I haven’t had to do that for a long time.’

A universe of languages

It is bright and sunny in Sulaiman Addonia’s dark room when we sit down on one of the benches at the end of August. Behind us passes the Babelian confusion of tongues that so characterizes Brussels: noisy Dutchmen, softly talking Arabs, a singing Congolese, a French-speaking family with a disobedient dog.

Silence is about language. Saba, the female main character, wonders at one point how the refugee camp robs someone of their language, ‘as if it were meat on bones. She could visualize the hemorrhaeging of her words, everyone’s words. No one without language is alive’.

‘Hagos may have been born mute, but their society turned every child into one.’

It is a remarkable sentence because the male main character, Saba’s brother Hagos, is mute. But, Saba thinks in another moment, ‘Hagos is not mute. The world is not prepared to listen’. And a bit further, she thinks: ‘Hagos may have been born mute, but their society turned every child into one.’

Silence becomes a language and language becomes empty, in the extreme conditions of a camp, I say. ‘Not only there,’ Addonia responds. ‘The individuality of children is silenced in every society, in every tradition.’ ‘And at the same time, everything is language,’ he adds: ‘Music is a language in itself. And the bubbling water of the pond in front of us is a language that I listen to and try to understand.’

Towards the end of Silence, the reader is confronted with a statement in capital letters, as if it were an angry message on Twitter: ‘When you learn a language as an adult, words are like razors on your tongue. The sentences you utter are so wounded that they fall apart when they leave your mouth.’

This is a succint summary of an essay that we also published in MO* and in which Sulaiman Addonia also says that every new language is a trauma, partly because it displaces the previous language, with all its memories. Yet he decided — after years of resistance — to learn Dutch.

Sulaiman Addonia: ‘I wanted to finally look my fear of the new language, which surrounds me in this country, straight in the eye. A bit like someone who is afraid of heights but decides to climb a mountain. I’m not sure I’ll succeed, but I really want to have tried. But it also has to do with the fact that I have started to feel like a real Bruxellois. I have contributed my bit — my art — to this city and so I have become part of it. It was not a coup de foudre, but a slow and silent love. A new, complicated relationship.’

‘I was migrating less to Brussels than to the imagined place in my head where a story needed to take shape.’

In another interview, Addonia once said that he felt like a Londoner the day he arrived there as a minor asylum seeker. So why did it take him more than a decade to start loving Brussels or Belgium? What is so difficult about this place?

‘It had less to do with Brussels and more to do with myself,’ he says. ‘I had been on the move since I was one and a half: from home to the camp in Sudan, on to Jedda in Saudi Arabia and then with my brother to London. Brussels was the move I could not take anymore. I was tired of it. And then there was that book that wanted to be written. For that, I had to step out of the queu of life for quite a while. At that moment, I was migrating less to Brussels than to the imagined place in my head where a story needed to take shape.’

‘The book rewrote me’

To just about every question about the characters of Silence is My Mother Tongue — Saba, Hagos, the midwife, the judge, the businessman, the voyeur, the prostitute, the grandmother – Sulaiman Addonia can provide not more than half the answer. ‘I did not shape them according to my preference or to serve my narrative. They wrote themselves.’ That sounds very literary, but how do you do that?

The most important step, says Addonia, was to suspend his own judgment. And he gives the example of Jamal, the man who builds a cinema in the refugee camp, with a hole in the middle of the sheet through which he can peek at Saba. ‘I had to break away from my aversion to give him room to become himself.’ Hagos was easier, he got developed in the dark room of the streets of Ixelles, complete with his speech disability, his feminine features, his own sexuality. Hagos is not a metaphor, he just is.

‘The most important step was to suspend my own judgment.’

‘Ultimately, it’s about allowing yourself to write from your subconscious, not from your socially formed consciousness. It’s not what should be that’s important, but what can be.’

This is clearly the adage of the characters who populate Addonia’s refugee camp. Certainly Saba and Hagos break out of the gender expectations, restrictions and commandments imposed on them by tradition. The fluidity of gender and sexuality is the rigeur in cosmopolitan novels today, but unexpected when the story is set in an African refugee camp.

Does the subconscious of the worldly writer bubble to the surface here, or does the story nevertheless reveal a reality that we simply do not know? ‘Rather the second,’ replies Addonia. ‘It is the complex reality of people, and it is no different in Brussels, Jedda or a refugee camp in the harsh interior of Sudan. Of course there are people with fluid sexuality in a refugee camp. Or feminists, like my grandmother. It’s just that they don’t name those feelings or attitudes or do so differently than here in the West, and maybe that’s what makes it so hard to recognize them. When we take off the Western glasses, we see more.’

‘To empathize with the various characters, I had to accept their freedom. That made me a freer person.’

If Sulaiman Addonia had to suspend his own judgments to allow his characters their freedom, how does he deal with people in everyday life who don’t conform to what is called normal? ‘I wrote the book, but the book rewrote me,’ he answers.

‘To empathize with the various characters, I had to accept their freedom. This effort then made it easier to accept people in their stubborn individuality even outside my imagination, in the city or wherever I went. Apart from the norms, prejudices and expectations that I myself naturally carry within me. I have become a freer person.’

Let’s talk about sex

If the struggle against tradition – according to Saba ‘the third religion in the refugee camp’ – and gender roles is the central theme of Silence, then sex is the driving force of the story. Addonia is very reticent in describing sex, yet every character, every place, and almost every development in the story is drenched in sexual desire. Why?

‘Why not?’ he asks. ‘Because the story is set in an African refugee camp? Surely I couldn’t stop two characters who wanted to go to bed with each other on the grounds that the reader doesn’t expect that in a refugee camp?’

Every character, every place, and almost every development in the story is drenched in sexual desire. Why? “Why not?” he asks.

Sulaiman Addonia: ‘Most stories about Africa are shrouded in Epic Themes: war, corruption, exploitation, colonial oppression. I undressed the African characters, stripped them layer after layer of those big themes, until I arrived at their naked bodies. The result is a story that revolves around intimacy. The human person, his or her body, his or her own dreams and experience of sexuality, love and intimacy. The ordinary person, somewhere in a house or a hut.’

‘No one is a virgin only once,’ says the grandmother, as she recounts how she made her husband to spend nights exploring her body rather than allowing him to “jump on her” immediately on the wedding night. And she continues, ‘With every new lover, we turn virgin again. Because it is not a hole you make love to but a body, a mind, and a heart.’

Just as the meaning of language transformed, so for Addonia, while writing, sex changed from its reduction to penetration to a range of touches or fantasies, and even into a spiritual experience.

Sulaiman Addonia refers to the scene in which Saba goes to Jamal in his cinema, ‘to make his fantasy come true, because it was hers too.’ The intimacy of that encounter is described on one page with such poetic tenderness that, as a reader you understand what he means by the shift to a spiritual experience. In Jamal’s words, ‘Saba rearranged herself, spreading her map of love over me. This is our time, she said. This is my time.’

A glass ceiling

Life (in the refugee camp), however, is not made up of high points or deep experiences, but of banality and boredom. ‘We all entered this camp as humans, but only some of us would leave so’, Saba reflects, just before she exits. When I ask Addonia how and in what way a refugee camp, or more broadly: the experience of being a refugee, dehumanizes people, he hesitates.

It is a reflection of Saba, not necessarily the experience of the writer. On the contrary almost: ‘People always have the possibility to become who they want to be. In fact, when I started writing the story, I saw the camp as a kind of opportunity to start all over again, without the ballast of history and tradition.’

Refugees have an endless amount of time, which makes it lose all value. And tradition, to distinguish right from wrong.’

Perhaps, I suggest, someone who has to leave everything behind is also someone who lacks what you need to reimagine yourself completely? That’s right, he says. ‘Indeed, the reality is that all those destitute families seem to have only two things left. There is an endless amount of time, which makes it lose all value. And there is tradition, as the only beacon to distinguish right from wrong.’ That distinctly patriarchal tradition is embodied in the novel by a man and a woman, the judge and the midwife.

In that tradition, Saba notes, women are placed on a pedestal on the one hand and expected to be invisible on the other. Is that perhaps the experience of any group that is not at the center of power? That they are tolerated as long as they conform to prescribed expectations and do not demand visibility or self-determination too explicitly?

‘Indeed’, Sulaiman Addonia responds. ‘Even in London, where you are given the explicit promise that as a migrant you can become a full citizen – something for which I am immensely grateful – you still encounter boundaries at some point. The glass ceiling exists, not only for women, but also for those who are black. “Up to here, and no further”: what is unwavering law in a country like Saudi Arabia, also pops up elsewhere as an implicit threshold.’

It is against these restrictive norms that Hagos and Saba fight. They reject the certainty offered by tradition and thereby embark on a journey of uncertainty and unpredictability. Can people survive without clinging to the values handed down from previous generations?, I ask. ‘They are trying,’ concludes Sulaiman Addonia.

Maak MO* mee mogelijk.

Word proMO* net als 2798 andere lezers en maak MO* mee mogelijk. Zo blijven al onze verhalen gratis online beschikbaar voor iédereen.

Meer verhalen

-

Report

-

Report

-

Report

-

Interview

-

Analysis

-

Report

Oxfam België

Oxfam België Handicap International

Handicap International